Jonas Ropponen in interview with Anna Metcalfe

Pubism 15 January – 1 February 2015

Chapter House Lane

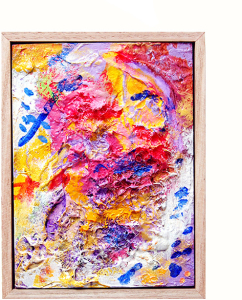

Jonas Ropponen

Loose Portrait

20cm x 15cm

polymer activated gypsum, pubic hair, acrylic, oil on found board. 2014

22 January 2015

AM: Jonas, you’ve described the series of artworks in ‘Pubism’ to be ‘as much an investigation into colour and studio materials and processes, as they are repositories of my DNA’.

These works feature your own hair, fingernails and bodily fluids, and this is juxtaposed with really joyful combinations of colour. What’s your intention when combining bright colour and bodily material together like this? What interests you about it?

JR: I enjoy using bright colours and heavy textures because they have a strong pull on the eye. I think, like many artists, I enjoy letting the nature of the materials have a say in the making of art. There is an intuitive manner to making my work that I’ve learnt not to weigh down with too many rules or explanations. In Pubism I worked quite spontaneously over the surface of my paintings and worked on more than one at the same time. Giving myself over to quick gestures and spontaneous decision making when it came to composition and colour went hand-in-hand with allowing myself to incorporate untraditional materials in the painting surface. I didn’t think too much about mixing in my bodily detritus and discarded consumer materials, it just seemed the right thing to do. Often, when I paint I get a loose brush hair in the paint. I think including body hair in my painting grew from that. Before I knew it, I had put not just my scalp hair, but also my pubes in my paintings, and that information is now on the Internet for future employers to read about.

AM: Are you interested in the tension between being appealing and repellent at the same time?

JR: Yes, I enjoy that dynamic. I wrote my Masters exegesis on the grotesque and confessional modes in art. The grotesque, as an art term, indicates an awkward tension between opposites such as the attractive and repellent, humorous and horrific, sexually carnal and transcendent motifs, etc. The grotesque introduces a kind of uneasy movement in an art experience and often incorporates depictions of forms in transition or exaggerates compositional elements. I don’t mind a low level of discomfort going on in my artwork and I like that if you spend a bit more time with a piece it may move you around a bit. Even though I put repellent things in the paint (like fingernail clippings) it’s not so much about showcasing disgusting things as it is about an aesthetic push-and-pull. I’m also not particularly interested in making grossly offensive, attention seeking pieces. I don’t want to be the ‘pube guy’. I’m becoming more and more drawn to producing ‘schmick’ fetishised art objects over looser installations because I enjoy the grotesque strategy of polarities. In the future, I see myself amping up the finish of my frames and lustre of my surfaces and marrying these with further abject elements.

AM: Can you talk to us about your process in creating this series of artworks and the other materials and objects you’ve incorporated?

JR: I did my undergraduate in printmaking and have a familiarity with working not only in 2D, but with paper as a material. When I moved into making sculptural installations I found I made a lot of work out of papier mache. This can be quite a sloppy process. In my show at Chapter House Lane, I mixed paper pulp in with polymer-activated gypsum together with my body hair and fingernail clippings collected and applied it onto boards with my hands. I painted on this substrate with acrylic paint. I worked fast on a number of paintings at once, making intuitive decisions on composition. This took a number of weeks to complete.

I am red-green colour blind and enjoy working with colour as it’s a challenge to visually understand what’s going on with each painting. The visual field gets confused a bit, especially when the hues are light or dark. I like for colours to flicker through from the underlying layers. By not working figuratively, the colour becomes more important to me compositionally. It’s challenging not to feel fully in control visually and difficult to know when to stop the over-painting process.

AM: What attracts you to found objects?

JR: I think the space between something being valued and something considered rubbish is interesting. I use found timber a bit. Often it lies around in spaces like nature strips or in my studio workshop – not quite in a rubbish pile and not quite set aside for some other project. I find it fascinating that things like fingernails and hair can be highly valued when on a body but considered disgusting the moment they’re cut off the body. I like returning these discarded elements to a place of value.

AM: At what point did you decide to use the drop sheet in the show?

JR: During the making of my six 50cm x 45cm paintings on board that I presented together in one of the window spaces, I noticed the found carpet I was using as a drop sheet was taking on some nice patterns. I painted all my work on the floor. I found the mixture of geometric shapes and splatter marks left over was pleasing. I also brushed off excessive paint from my brushes onto the carpet before washing them up, and voila! I had a new work. I tried not to be too mannered about the placement of the paint, but at times I became distracted by deliberate daubing.

AM: There’s something very personal about these works, not only in that they include your DNA, but you’ve pulped Watchtower magazines and used them for texture, which is a nod to the fact you grew up as a Jehovah’s Witness. They are very organic and honest. At the same time, you produce very different work under alter egos such as Federico Joni and Sven Eriksson. Can you tell us about these aspects of your work?

JR: I have worked part time in administration at a sexual health clinic for over a decade and am probably quite desensitised by regularly talking about sex, sexuality, ulcerated genitalia and contraception without blinking to not think twice about the inclusion of pubic hair and semen in my work. Like the pubic hair, the use of Watchtower magazines is a bit of a booby trap in my work. It’s easy to focus in on the sensational stuff and be under the impression that ‘that’s what the work is about’. I grew up as an immigrant in Australia and my family were Jehovah’s Witnesses – a strict and unforgiving sect on the Christian fringe. I was a pretty devout teenage door-to-door preacher before I came out as gay, was excommunicated and lost my parents, brothers, relatives in Scandinavia and my former friends. After a decade or so of being an independent person I felt an urge to revisit this experience in my artwork through narrative writing. This was an awkward process to share professionally as an artist, because, as much as contemporary life has a certain ‘tell all’ bent to it at the moment due to the rise of social media, a confessional mode in contemporary art is not really ‘in’. There is a bit of earnestness in my work, I’ll wear that. The Watchtower Bible and Tract Society (Jehovah’s Witnesses) is one of the biggest publishing houses in the world. Their bimonthly flagship publication, The Watchtower, is printed in something like 18 million copies and in approximately 230 languages. I find the magazines everywhere! They haunt me a bit. I ‘ve enjoyed pulping them down, mixing the goop with other types of goop and painting over the stuff with other stuff. You could probably make a case for me not taking a very subtle approach in my practice, but those magazines represent a big part of my past that I have had to integrate somehow. Maybe this is all just self-directed psychotherapeutic sand play!

I like to think of my works as repositories, not only of my past, but of my DNA. I sometimes wonder (in the most humblest of ways) about my artistic legacy. When I die, what will be left? I like to think that my DNA will go on with my works. My paintings are like fossils.

To avoid too much focus on my personal life I’ve worked under pseudonyms in the past. They’ve functioned as a sort of pressure valve – a space in which I can explore other ways of making and other themes. I worked for six years under the name Federico Joni who had a performative element to his practice. I currently make work under the name of Sven Eriksson. The name is a gesture to my Swedish heritage – Sven Eriksson being a very common Swedish name, but one that seems a tad exotic here. My own name often gets mispronounced. What is familiar to me is strange to others. Sven’s works are large, highly detailed linocuts. His pieces are very figurative with a lot of information on the picture plane. As I make them I am aware of how one foul slip could compromise the work. It’s a very different way of working than my hectic painting practice. I find it very relaxing.